Michael O’Neill (1953 – 2018)

Michael O’Neill 1953-2018

Michael O’Neill who has died of cancer on 21 December 2018, aged just 65, was one of the most brilliant scholars of Romantic and twentieth-century poetry of our time, and an acclaimed poet whose five published collections attracted high praise and national awards. During a distinguished academic career spanning some forty years at Durham University, Michael was twice Head of the Department of English Studies (1997-2000, 2002-2005) and a founding Director (Arts and Humanities) of the Institute of Advanced Study. His critical and editorial interests were initially based in his lifelong admiration for, and unrivalled knowledge of, the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. His broader engagement with poetic self-consciousness and poetic dialogues between Romantic and Modern verse extended into his day-to-day life: he was a Founding Fellow of the English Association, and served on the editorial boards of Romanticism, the Keats-Shelley Review, Romantic Circles, Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, and The Wordsworth Circle. He was also Chair of the Wordsworth Conference Foundation until shortly before his death, and a member of the International Byron Society’s Advisory Board.

Michael was born on 2 September 1953 at Aldershot, where his father Peter was a surgeon and his mother Margaret a GP. He was the eldest of seven brothers and sisters. When in 1960 the family moved to Liverpool Michael attended St. Edward’s College, excelling across all subjects and also establishing a reputation as a formidable rugby-player and, at cricket, a canny spin bowler. In 1972 he won an Exhibition to read English at Exeter College, where he was tutored by Jonathan Wordsworth who, though ‘puzzled by [Michael’s] love for Shelley’ became a lifelong friend. Michael graduated with a double first and went on to write an Oxford D. Phil on Shelley, supervised at New College by John Buxton; his thesis was published in the Oxford English Monographs series as The Human Mind’s Imaginings: Conflict and Achievement in Shelley’s Poetry (1989) — ‘undogmatic, demandingly precise in its readings, and genuinely enhancing of one’s experience of the poetry itself’ said Kelvin Everest in the Modern Language Review.

When Michael first met Posy McKendrick she was a next-door neighbour at Liverpool, the sister of his lifelong friend and fellow poet Jamie McKendrick. Michael and Posy kept in touch as undergraduates (she was studying at Cardiff) and they married in 1977. Over 42 years, they based themselves in Durham with their son Dan, now an academic at Nottingham University, and daughter Melanie. A granddaughter, Millie, joined the family in 2012: Michael was devoted to them all.

In 1979 Michael was appointed by J. R. Watson to a lectureship at Durham University, and began an academic career that influenced the lives and careers of generations of students, some of whom have gone on to become eminent scholars themselves. Through teaching, supervising, examining dissertations, reading and assessing journal submissions, book manuscripts, grant applications and promotion applications his influence within the profession and beyond it was immeasureable, and always conducted with the same care that he brought to his scholarly and editorial projects. As his colleague Sarah Wootton recalls: ‘Michael’s contribution to the curriculum he shaped was unique and uncommonly wide ranging, from his inspiring seminars on Keats and Shelley to lectures on The Book of Job, Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night to nonsense literature and the poetry of Hart Crane. Of the overwhelming and moving testimonies written by Michael’s former and current students since his death, two themes recur: his lectures, particularly to first-year students at Durham, provided an invaluable foundation and instilled a passion for literature that extended well beyond their degrees; the impact he had on the many PhD students he supervised and the scholars he mentored was life-changing’. Michael’s former PhD student Madeleine Callaghan, now lecturing at Sheffield University, also speaks for his life-changing impact: ‘Michael didn’t teach his students to think like him; Michael taught them to think well for themselves. He taught his students to come to a poem on its own terms, to take pleasure in uncertainty, and to take risks imaginatively. He showed his students by his own example that poetry must be at the fingertips, felt on the pulses, and central to life. His endless generosity, luminous intelligence, and fascination with literature, made being his student the single greatest privilege a lover of poetry could experience’.

Over his long career Michael published an unrivalled range of scholarly essays, books and editions. Shortly after The Human Mind’s Imaginings he published a Literary Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Then came Romanticism and the Self-Conscious Poem (1997), a brilliant study of poetic self-awareness that ranges from the works of Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Shelley, to Auden, Stevens, Yeats and Clampitt. Reflecting Michael’s interest in poetic influence and inheritance, The All-Sustaining Air: Romantic Legacies and Renewals in British, American, and Irish Poetry since 1900 (2007) cast widely across transatlantic poetry, linking the Romantic and the contemporary in the poetry of Stevens, Heaney, Mahon, Muldoon, and Hill. Seamus Perry recalls that Michael ‘wrote a fine companion to Yeats and also a very good book about the Auden group with Gareth Reeves; and that itself shows something of his wonderful critical catholicity since the 30s poets tended to disparage Shelley so much’. Heidi Thomson also observes that ‘all of Michael’s books are masterclasses in the close reading of poetry: with extraordinary critical skill and verbal insight, he articulates what many of us may have caught glimpses of but could never have expressed so richly’. As a widely published poet himself, Michael could feel poetry on his own pulse – an insider of poetry’s craft and art. When he died he had just completed the proofs of a major new book, Shelleyan Reimaginings and Influence: New Relations, to be published shortly by Oxford University Press. Appearing some thirty years after Michael’s first book on Shelley, this new study draws together the scholarly concerns of a lifetime: ‘the book’, says Maddy Callaghan, ‘reveals Shelley’s poetic subtlety to grow out of his responsiveness to his predecessors and peers, and Shelley’s significance as an influence to be based on his openness to his reader’s own interpretative modes. For Michael sought to allow Shelley’s voice to lead him into new ways of understanding the Romantic poet: Michael’s erudition, insight, and vitality made him an ideal reader of Shelley, and one to whom Shelley could entrust the “electric life” of his poetic thought’.

Michael’s own poetry received an Eric Gregory Award (1983) and a Cholmondeley Award for Poets (1990). He was a founding co-editor of Poetry Durham (1982-94), and his own collections included The Stripped Bed (1990), Wheel (2008), and Gangs of Shadow (2014). After his diagnosis of oesophageal cancer in the autumn of 2017 Michael responded to the poor prognosis with exceptional bravery. The vicissitudes of illness and loss, coupled with his drive to inspired survival, were articulated in some of his finest poetry collected in his fourth collection, Return of the Gift (Arc, 2018), which received a Special Commendation by the Poetry Book Society. Michael gave many public readings of his own work during his last year, performing his verse with gusto and grace. The poems that address his illness are enlivened by wit as well as courage, without disguising the bleakness of his situation or relinquishing the acute observation that is a hallmark of all his work: ‘I couldn’t think except through literature / which gave me guises, methods of response, / a way of cloaking the brute fact of cancer, / implausible, I grant, but a defence’ (from ‘Those Days’ in Return of the Gift). As Heidi Thomson remarks, ‘Michael’s poetry readings, I realize now, were a gracious form of leave taking, of giving his family, friends and colleagues a token of what he wanted to be remembered by’. A final collection of poems, Crash and Burn, draws on the experiences of his last year living with cancer; it will be published by Arc in April 2019.

Michael had an extraordinary genius for masterminding and executing large editorial projects, evidence of his superb diplomacy and ability to deal with a wide range of people at various stages in their careers. Unfailingly courteous, precise, and encouraging in his guidance and responses to contributors, Michael published, among many other works, Literature of the Romantic Period: A Bibliographical Guide (Clarendon, 1998), the definitive Cambridge History of English Poetry (2010), and John Keats in Context (Cambridge, 2017). As remarkable are his achievements as a textual scholar-editor, in his editions of Shelley for Oxford University Press (2003) and Johns Hopkins University Press (2012), in addition to his collaboration with Donald Reiman on the fair-copy manuscripts of Shelley’s poem for Garland (1994). On the 5th of January this year Michael was honoured posthumously with the Distinguished Scholar Award of the Keats-Shelley Association of America at the MLA Convention in Chicago.

Off the page, Michael had a wonderful gift for elucidating the intricacies of poetic form and poetic dynamics. His keynote lectures, conference papers, and poetry readings always conveyed the passion and the intellectual engagement of a superb close reader at work. His handouts, sometimes on A3 paper to accommodate his many quotations properly, and often consisting of various collated pages, were legendary. They were treasure-troves of pleasure and interest, juxtaposing lines of Shelley, Wordsworth, or Keats, with verse by Bishop, Stevens, Clampitt. Always he resorted to close reading, charging mostly canonical texts with renewed life, making them new through interactive interpretive engagement. He never forced a poem into a rigid interpretation of his own making; instead, he allowed the poem itself to do the talking, acting as a mediator for the various sounds, techniques, and formal configurations that make up meaning.

I first met Michael O’Neill in 1991 at the Red Lion Hotel at Grasmere during the Wordsworth Summer Conference that year. Michael was lecturing, I recall, on ‘Byron and Romantic Self-Consciousness’, and his lecture was subsequently published as an essay in The Wordsworth Circle. Since then we met every year, here or there, at conferences and seminars, and most recently at the ‘Encountering Malta’ series held in the Old University at Valletta – a city that held a special magic for him, particularly the Upper and Lower Barrakka Gardens, and late hours at the Jubilee Bar in St. Lucia Street. Peter Vassallo, Professor and former Head of the English Department at the University of Malta comments: ‘Michael first came to Malta when I had invited him as our External Examiner about fourteen years ago. He stayed at the Hotel Castille in Valletta which he loved and where he enjoyed his English breakfast on the roof of the hotel overlooking the Grand Harbour’. Recalling the annual vivas for graduating students, Peter says that Michael ‘had a special way of making nervous students feel at ease and would ask searching questions in such a pleasant and gentle manner. On one particular occasion a student was told by a member of the examining board (which I was chairing) that there was a glaring error of fact in her dissertation on Machiavelli in Elizabethan drama which asserted, wrongly, that Machiavel appeared on the stage in Edward II, whereas it should have been in the Prologue to The Jew of Malta. The student’s reaction was “yes, I know I made a mistake! Can’t anyone make a mistake in this University!” Later that evening over dinner at home Michael with his customary chuckle told me “I must say I admired her chutzpah”. He came over to Malta as a guest speaker quite frequently to the Conferences on “Britain and Italy” we had convened and I particularly recall his superb paper on Shelley’s Dante which he delivered with verve’.

Another fruitful development from Michael’s connection with the University of Malta is recalled by Ivan Callus, Professor of English: ‘Over the years, Michael’s brand of genial erudition and openness to diverse approaches to literary studies meant that he developed a fine rapport with scholars from a number of European universities. He had a particularly strong and longstanding relationship with the Department of English at the University of Malta and with the Institute of Anglo-Italian Studies there, in whose conferences about Romantic and comparative literature he was a keen and much valued regular participant. Latterly he also helped foster the Department’s journal CounterText, launched with Edinburgh University Press in 2015 and whose first associated conference – intriguingly, on the subject of “The Poetic” – he co-hosted in Durham in the autumn of 2016. His contribution, in the form of a brief essay called “The Poetic: Brief Reflections on a Contradiction”, to a special issue of the journal that followed from the conference takes on a deeper resonance now. These lines, picked almost at random from a piece that is disarmingly open and unaffectedly profound, provide a flavour of his thinking on the poetic, to which he developed a lifetime’s study: ‘Always the poetic says in an undertone: “There was pain; here is the useless, possibly enduring compensation of words”. For readers who might wish to view the whole text and the ways in which it repeatedly turns back upon itself, never content with easy formulations on its topic but affirmative nevertheless, Edinburgh University Press has kindly agreed to make it freely accessible on the journal’s site (CounterText 3.2, in the section ‘Reflections on the Poetic’)’.

‘Was told today I have liver secondaries’, Michael e-mailed to me on 30 November last year: ‘prognosis weeks rather than months … I have a book on Shelley which I’m proofing and a book of poems Crash and Burn with Arc yet to go into publication. Think will just miss the STC deadline’ — he was editing the Coleridge volume for the Oxford 21st-Century Authors Series. In the face of sudden and irretrievable change, Michael as always continued to plan positively and creatively for the future. He is survived by his father and by Posy, Dan, Melanie, and Millie.

Nicholas Roe

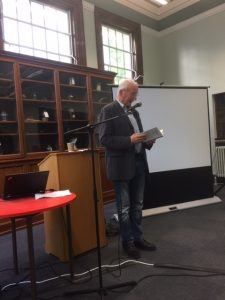

Michael O’Neill, reading from Return of the Gift at the Keats Foundation Conference in May 2018.